Article by:

Article by:

Sam Smith

I am a sketcher. I recently realized quite how much sketching defines what I do when someone pointed out to me that I rarely present any work without a pen in my hand. Whether I’m drawing on a whiteboard or quickly sketching on paper sketching that helps me to illustrate what I’m talking about. So it was an interesting challenge when I was asked to present a workshop at the Interaction12 conference in Dublin, where I would be doing the talking but the participants would be doing the sketching.

Looking at the number of workshops and presentations at the conference that were related in some way to sketching, and the number of people who have viewed my presentation slides on Slideshare (nearly 70k views in just over a week), I think it’s pretty safe to say that the perceived lack of sketching skills in the digital design community is something that has obviously touched a nerve. With all the rhetoric around collaboration with coders and clients through sketching, and the focus on lesser deliverables, this was obviously well timed.

I do believe that by breaking the ‘art’ of sketching down to a set of basic techniques that can be practiced, anyone can create sketches that not only do a good job of communicating but also look good. But before I dived into the practical side of the workshop I spent a bit of time asking people to think about 2 really important aspects that underpin all of the techniques that I was about to share: ‘what is a sketch?’ And ‘why sketch?’

What is a sketch? (and what isn’t?)

Firstly, and possibly most importantly, I like to make a distinction between sketching and drawing.

A sketch is not the same as a drawing in 2 important ways: execution and intent.

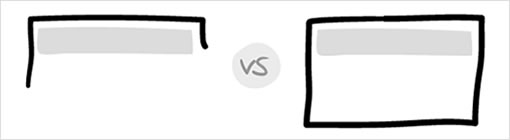

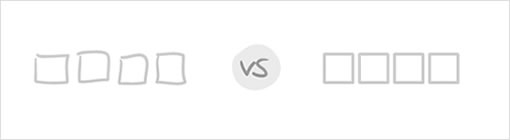

Aside from the obvious wiggly lines vs. straight lines type of differences, it’s easy to look quickly at something and decide whether it’s a sketch or a drawing. Quality and fidelity are easy markers but there’s more to it than that.

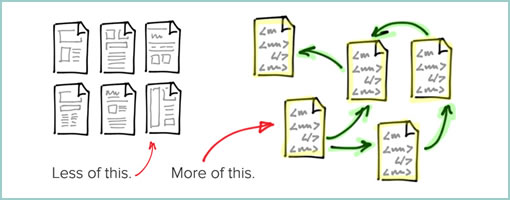

Unlike drawings, sketches aren’t precise and often include mistakes or corrections. A drawing is closer to a finalized design or idea. From a drawing you can get a good idea what the whole thing will look like. And that’s often what stops people picking up a pen. Half of the time when people are reluctant to sketch it’s because they are scared that their sketches will be judged by the same standards we use to judge a drawing or a polished design.

A good sketch doesn’t try to describe everything in detail (the bit that counts is ‘in focus’ and the rest is vaguely described for context), but it gives you enough information to get the point across.

When I sketch I’m not looking to create a beautiful, polished or even finished object (sketches can be beautiful, but they don’t have to be). What I’m trying to do is to capture an idea so that I can communicate it to others and explore whether or not it works. I’m not trying to do visual design on paper. We’ve all been in scenarios where the bottom line is boss and thinking time is seen as a luxury. If I’m spending time articulating all of my ideas in high fidelity on paper, it’s going to take way more time than I have.

The point of sketching is not to produce polished outputs, it’s to explore, challenge and validate ideas. That’s not to say that sketches can’t look good. They can, and with a bit of practice they will. But it’s not so much about what they look like as what they allow you to achieve.

Fast and free

I like to sketch because it’s quick and free (and not just in the financial sense). I can explore ideas on paper much quicker than I can in Illustrator or other tools and I’m not tempted to fall back on libraries of stock elements to solve problems because it’s easy.

Plus, the temptation in doing things digitally is to make things too neat.

When I am about to sketch on paper, knowing that it will be harder to undo, I hold myself back and think twice before the ink or lead leaves a mark … When I sketch electronically, this worry disappears as I know that I don’t have to generate the right ideas, but instead can easily correct myself if something needs adjusting. [Jakub Linowski]

Show your workings

I’m not against sketching digitally. If you can work as quickly as you can on pencil and explore as many ideas in the same way, then the medium isn’t really the issue. My worry is that working digitally encourages us to tidy up and erase mistakes, when often the mistakes are just as important as the final idea. If we are constantly hitting undo, all of those mistake are lost. We end up with a polished final sketch, but no record or evidence of how we got there.

When we’re reluctant to capture our ideas as sketches, often those ideas don’t get captured or aren’t explored as fully as they might be. Sketching is a really useful ideation and communication tool. The ‘art’ of sketching can be learned and practiced, but the real value is in the generating of ideas and the discussions around those ideas that sketches prompt.

Sketching shouldn’t always be solo

Jakub makes a really nice point in his piece on digital sketching:

Looking back, sketching has been wonderful at giving rise to design

representations that naturally act as conversation starters

I agree wholeheartedly with this. When I start to address a design challenge, my sketches are much looser and lower fidelity, but still enough to prompt and aid those conversations.

Sketches do not have to be pretty, beautiful or even immediately understandable by others. However, you should be able to explain your sketches and ideas when anyone asks about them.

– Sketching User Experiences [Saul Greenberg, Sheelagh Carpendale, Nicolai Marquardt & Bill Buxton]

Often the sketch will develop and evolve over the course of the conversation, as per Jakub’s point here:

Perhaps the use of paper can still be justified in collaborative sketching sessions when there‘s more than one designer at the table and the design activity happens simultaneously in real time.

I am a big advocate of this style, with one significant difference. I’ve seen this work successfully (and often) where the collaborators around the table aren’t just designers. Some of my most successful ideation sessions (for generating good design based around insight) have been when there have been designers, clients/stakeholders and developers all contributing and sketching – not just the designers.

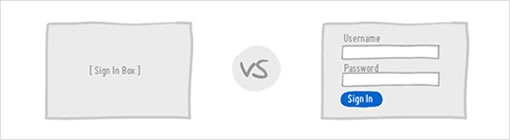

Part of the beauty of sketching is that it doesn’t look like the finished product. It’s like creating wireframes with ‘wiggly’ sketch lines to reassure the client that this isn’t what it’s going to end up looking like – except you’re actually sketching rather than making your digital version look sort of like a sketch. The key thing here is that people don’t mind scribbling on a sketch to show you what they mean. And then you’re on your way to collaborative design. Happy days.

Sketching in code

I heard the phrase ‘sketching in code’ mentioned more than a few times at IXD12. In his presentation, Jonas Löwgren talked about (and showed) how really complex interactions can sometimes be best communicated by building them out (show don’t tell).

Although I don’t disagree with this, I don’t think it’s always necessary when we’re dealing with less complex interactions, as many of us are compared to the things Jonas demonstrated.

Committing to building something (as opposed to sketching it) definitely restricts the way that I design. It certainly takes me longer to build it than to sketch it, and as a consequence I find myself exploring less ideas. Plus, if I’ve spent time building something, I’m more inclined to keep elements and re-use them rather than starting from a blank slate. Perhaps this is a symptom of me needing to get more comfortable in code the way I am encouraging people to get more comfortable with a pen or pencil?

Sketch more, sketch better

So, in short: sketching is good, mistakes are ok, neater isn’t necessarily better and when it comes down to brass tacks, good well thought through ideas are what counts.

Like anything, the more you practice, the better you’ll get. There’s more about what is/is not a sketch as well as some basic techniques and exercises in my Sketching Interfaces workshop sides.

Credits: Sam Smith

Article by:

Article by: